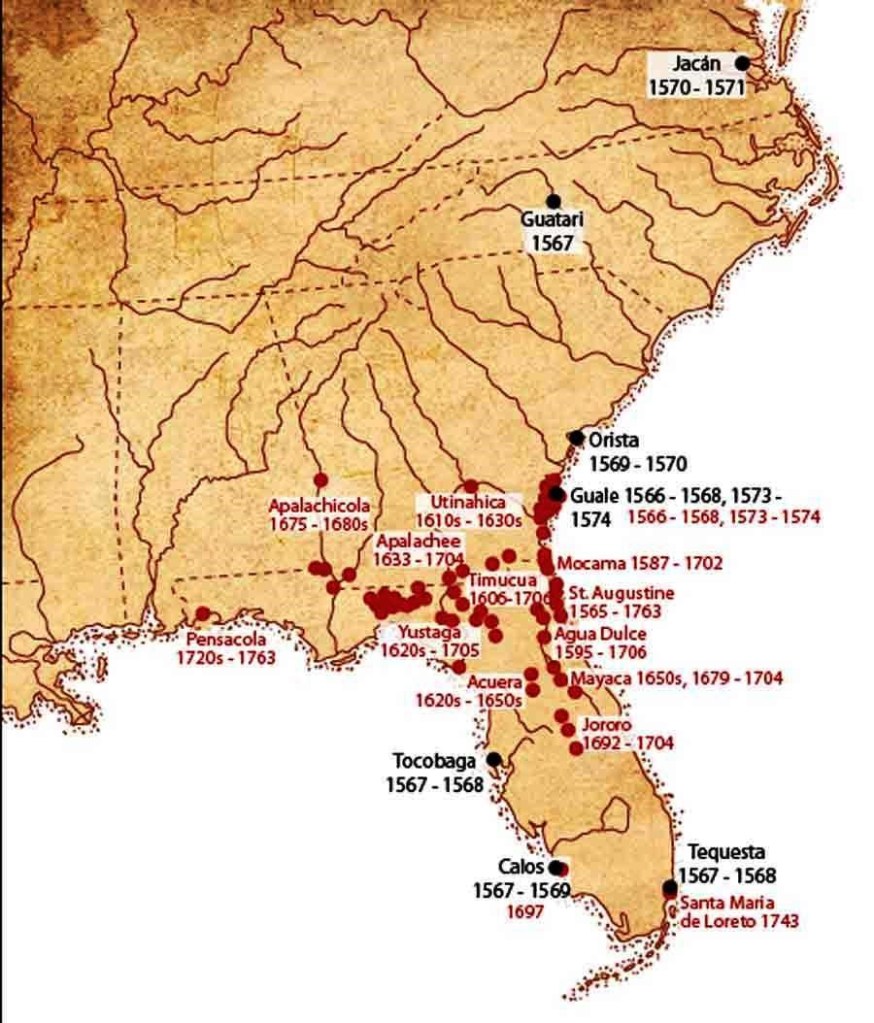

Florida Missions and Shatter Zone (1563-1763)

St. Augustine was the first permanent Spanish settlement in La Florida. It was established in in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés who was sent by Philip II to drive out a French Huguenot colony. For the Spanish crown St. Augustine would be a costly coastal frontier that would yield no returns other than its strategic location to keep European powers away. Its failure as a profitable colonial economic enterprise notwithstanding, a vigorous missionary effort was launched in the land with the Franciscan order at its helm. With significant toil and setbacks like the Indigenous uprisings of 1574, 1597, 1647 and 1656 against Spanish oppressive treatment, the friars’ constant quarrels with Crown officials, and the dire living conditions of La Florida, the Franciscans established missions among the Guale, the Timucua, and the Apalachee peoples that lasted two hundred years and extended from the Atlantic coastline to northern Florida and central Georgia.

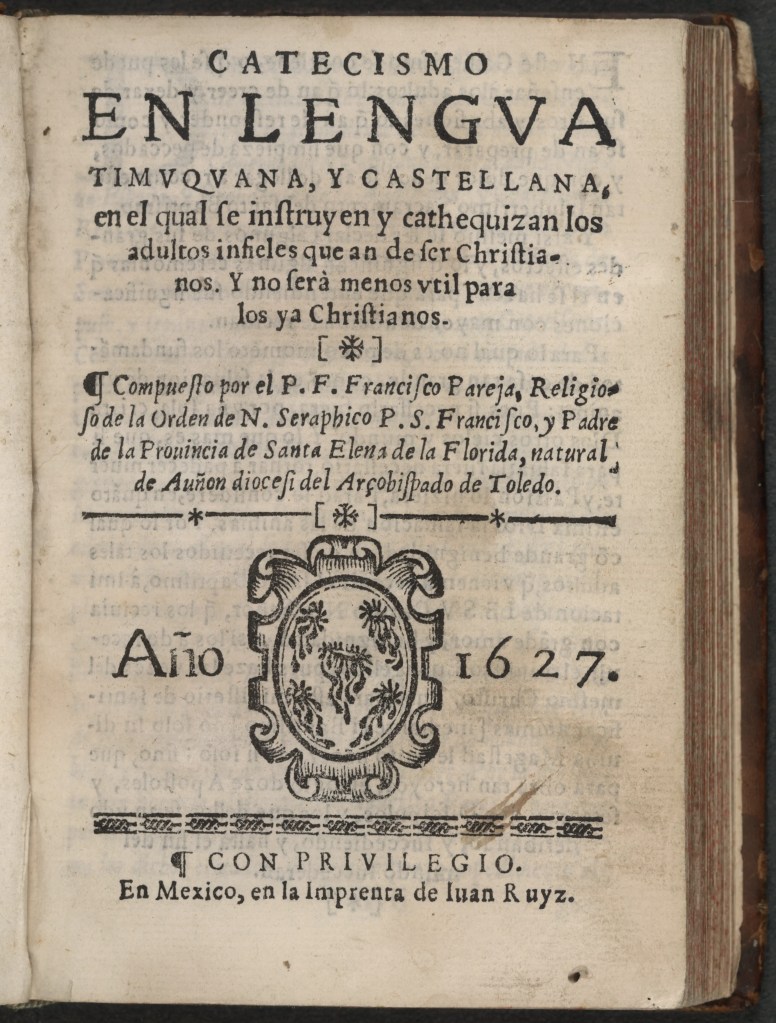

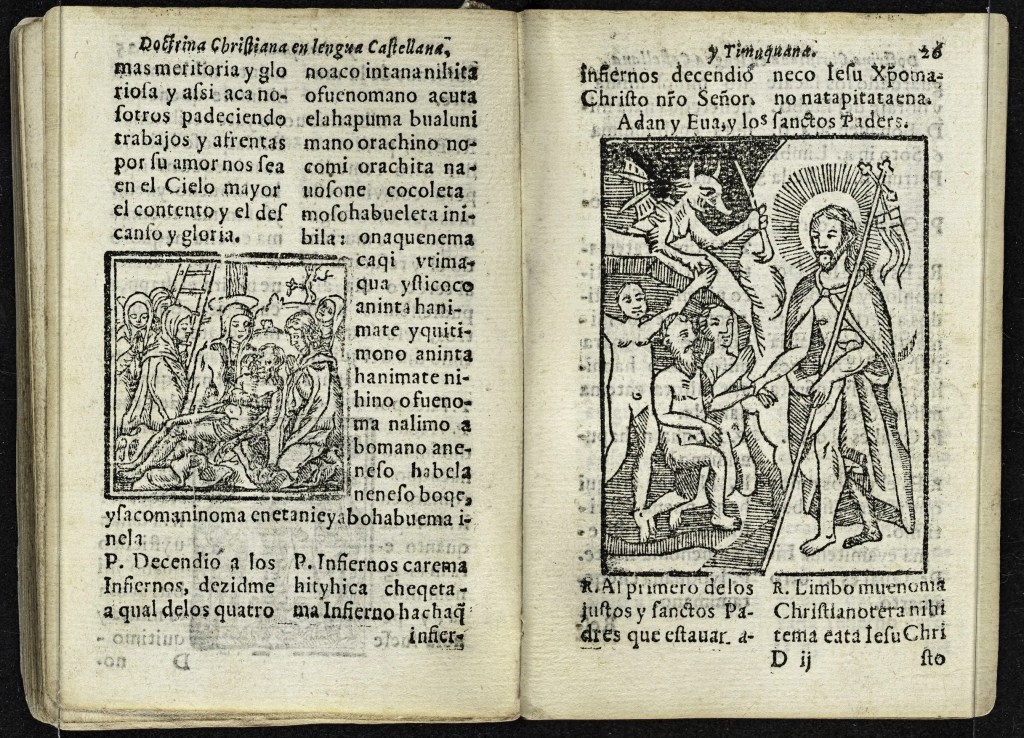

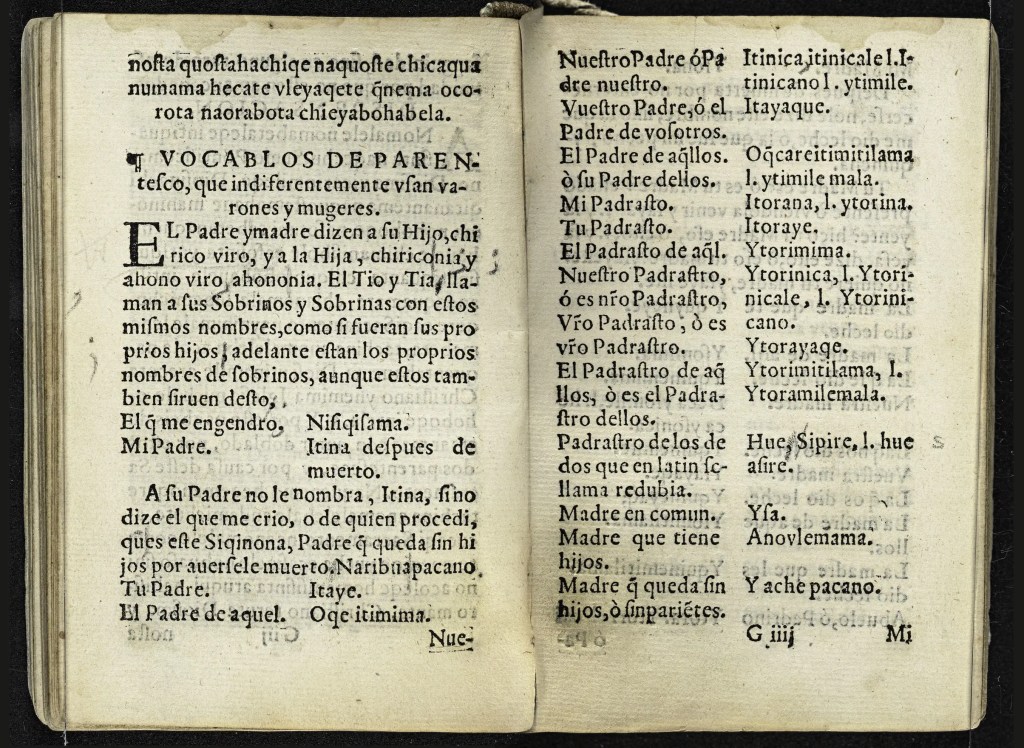

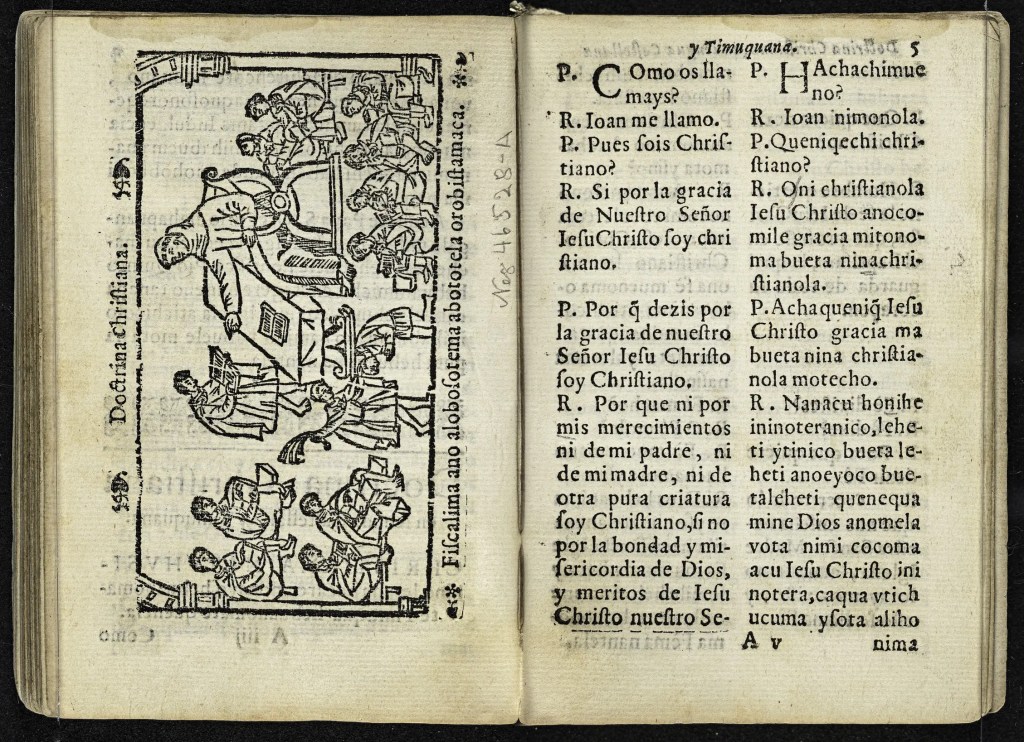

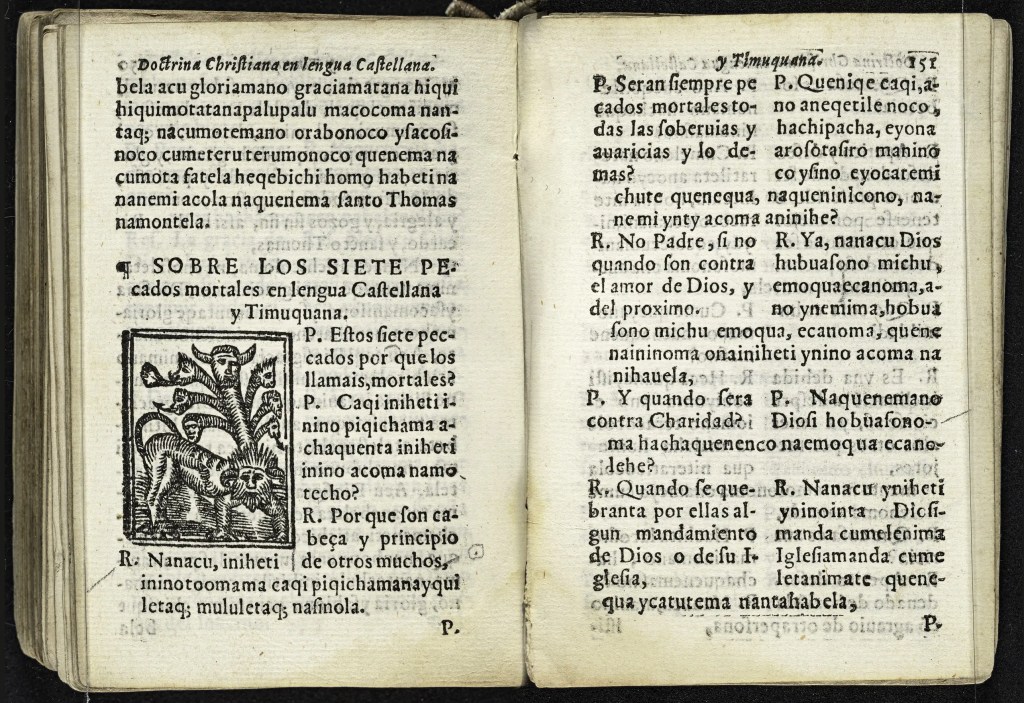

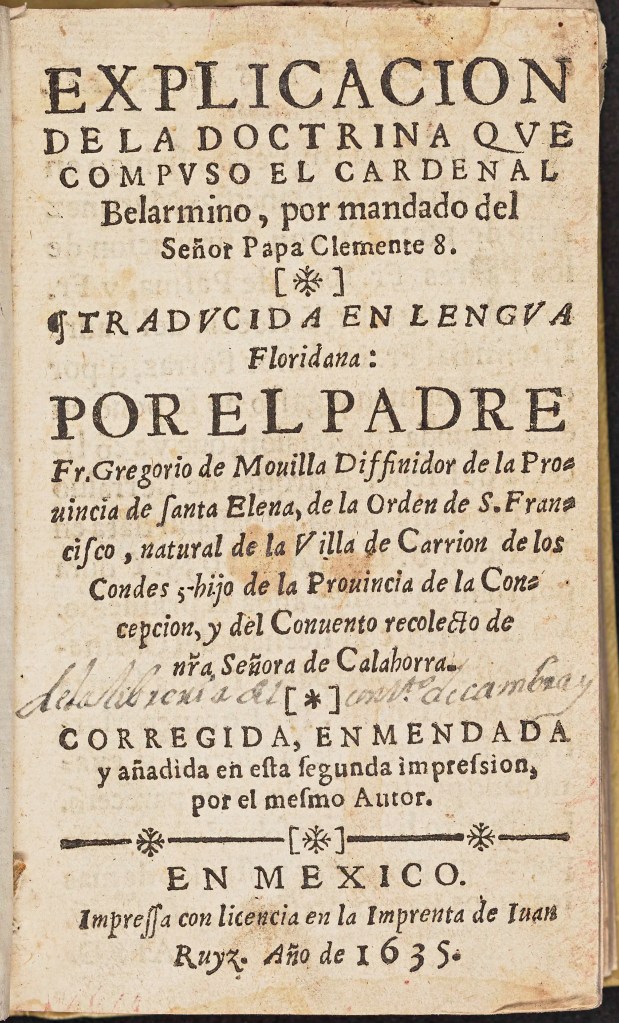

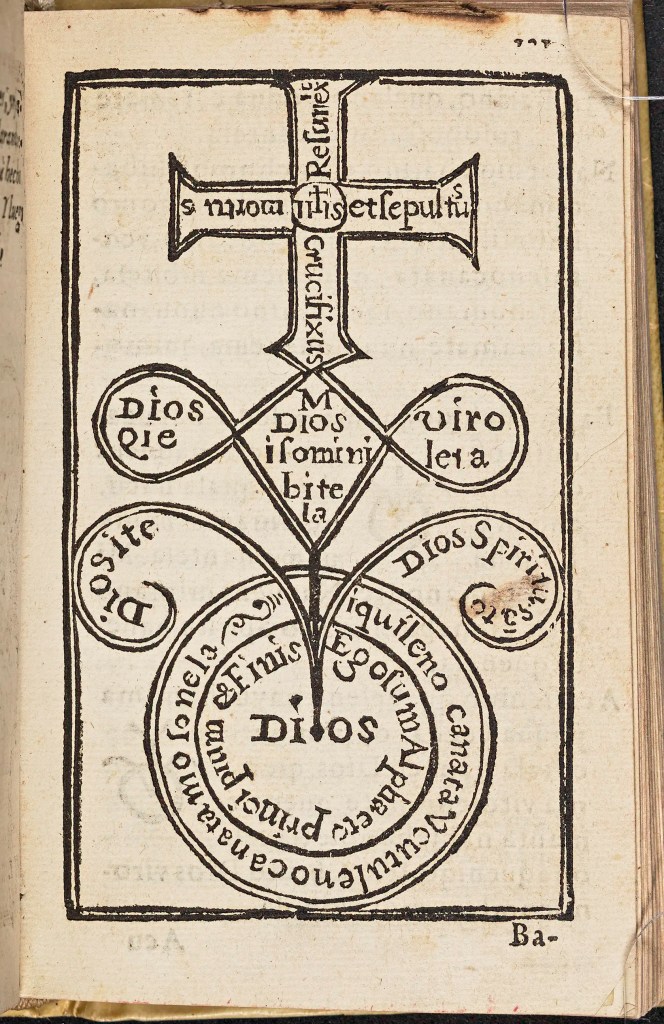

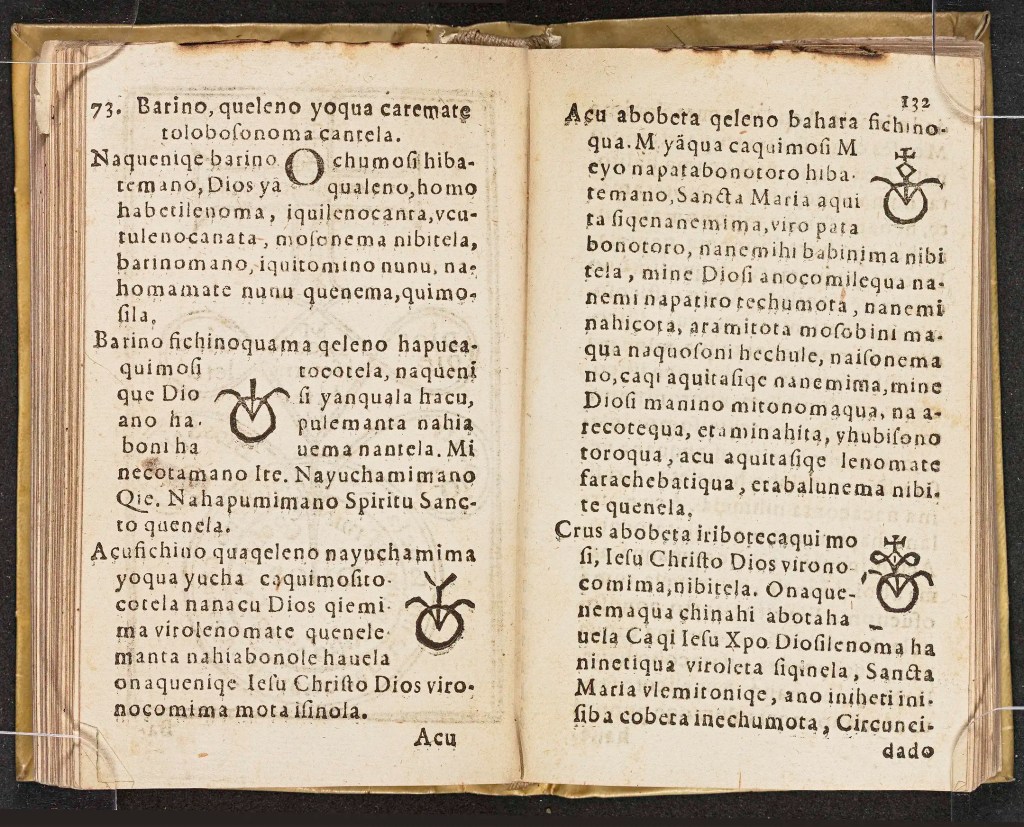

With the assistance of native speaker intellectuals, the friars learned the Indigenous languages and set them down to writing. There are nine extant imprints in Spanish and Timucua produced during the first three decades of the seventeenth century, making it the first recorded Indigenous language in present day United States. These bilingual imprints amount to a robust body of work that tells us important stories about cultural exchanges between the friars and the Timucua during the mission period. An extant letter in Apalachee written to Charles II in 1688 by Apalachee chiefs requesting a fort to protect the missions in the region evidences that the Apalachee language was also set down to writing. However, no other documents in Apalachee or Guale have been recovered. Some of the Timucua-Spanish bilingual imprints as well as the letter from the Apalachee chiefs are highlighted in this exhibition.

Tragically, due to epidemics, colonial exploitation by the Spaniards and the ravages of slave-raids by the English and their Indigenous allies, the missions had disappeared by 1763 when the Spanish swapped Florida for Cuba with the English. But the transcultural competence of the Guale, Timucua and Apalachee as they negotiated the globalizing epistemology of Christianity while preserving core aspects of their Indigenous identity is a significant element in Florida’s early modern legacy that needs to be explored, better known, and remembered.

Click on each image for the title and description.

The Missions of South Florida

Greek Cross or Tau style lead cross, 1684-1696.

29.9 mm, and a vertical height of 34.6 mm.

Mission San Buenaventura de Guadalquini,.

“Four arms are nearly equal in length, Post attachment rather than a loop for suspension. The site was excavated between 2007 and 2012 by University of North Florida archaeologists. The artifact is currently curated at the Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve (National Park Service) in Jacksonville, Florida.”

Image and text are courtesy of Dr. Keith Ashley, principal archaeologist, University of North Florida

Soon after the establishment of the city of St. Augustine in 1565, the Kingdom of Spain began establishing missions with military garrisons throughout La Florida to convert the Indigenous population to Christianity and secure control of the area from the French and English occupation. Friars of the Franciscan order set up self-sufficient villages where Indigenous groups were encouraged to live, taught Catholic beliefs, and learn European skills. Missions were established for the Calusa, Tequesta, Mayaca and Jororo of south and central Florida and the Guale, Timucua and Apalachee tribes of north Florida and South Georgia.

The Apalachee

The Apalachee are a Southeastern Woodlands people originally Indigenous to Florida, that spoke a now extinct Muskogean language. They maintained a highly stratified society of regional chiefdoms. Until the 18th century, they occupied an area around the Apalachee Bay, between Aucilla and Ochlockonee Rivers northward to todays’ Tallahassee.

The Spanish Explorers Arrive

The Apalachee first encountered Spanish explorers when the shipwrecked Pánfilo de Narváez expedition in search for gold reached their homeland in 1528 [only 4 of a crew of 300 survived a cross-country, 3,500 mile, eight-year journey that ended on the Pacific coast of Mexico].

Their next encounter with Europeans was in 1539, when the Hernando de Soto expedition wintered near their capital village, Anhaica. More Europeans followed and continuing conflict. Over the ensuing 70 years, internal strife, epidemic disease, and fear of attacks eroded the Apalachee’s faith in their leadership and traditional customs.

In 1607 some Apalachee began requesting Spanish friars to minister among their people. By 1625 there was regular trade to provide labor and provisions with St. Augustine. The Mission San Luis de Talimali (also known as San Luis de Apalachee or Mission San Luis), founded in 1633, was among the first established in the Spanish Province of Apalachee. Internal conflict between Apalachee factions and the Spanish authorities precipitated an Apalachee Rebellion in 1647. The deputy governor, his family, and several friars were killed but the chief [holata] of the San Luis Apalachee was not involved in the uprising and remained loyal to the Spanish.

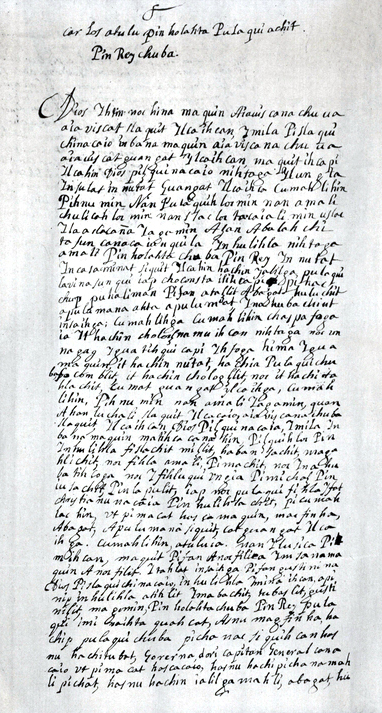

Letter written in the Apalachee language in 1688 to Charles II, King of Spain signed by six Apalachee caciques: Don Matheo, Chuba; Holahta Juan Mendoça; Don Bentura ybitachuco holahta; Don Alonso Pastrana, Casique de Pattali; Don Patricio Casique de Santa Cruz; Don Ignacio, Cacique d Talpatqui. Among other topics, the letter requests two forts to be built to protect the Apalachee from slave raids by the English and their indigenous allies. This is the only known extant text written in the Apalachee language. The location of the original is unknown.

Image courtesy of Special Collections in Richter Library at the University of Miami

In 1656 the chief [holata] of San Luis was asked to move his village to a hilltop site two miles west of present-day Tallahassee. The mission that was built was the only settlement west of St. Augustine. By 1675 it was a thriving community of Spanish and Indian farmers, ranchers, merchants, and trades people that survived for three generations. Apalachee served with Spanish soldiers in the Mission San Luis military garrison, protecting the Apalachee Province from rival tribes and their English colonial allies.

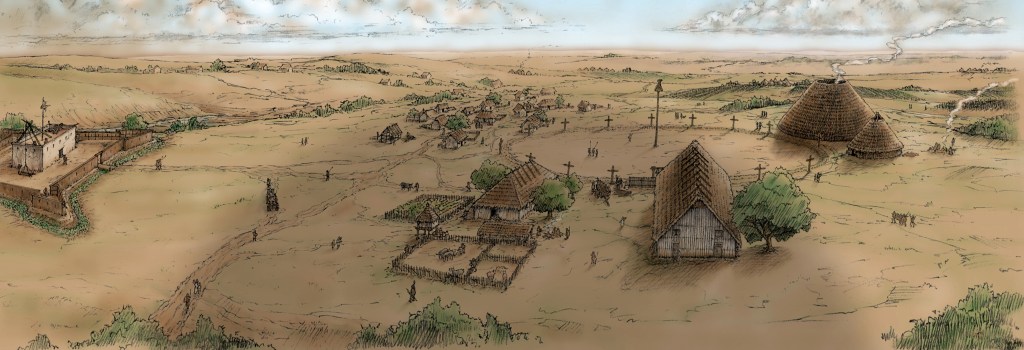

Text and image credit: Florida Center for Instructional Technology

When San Luis was built in 1656, the village resembled those that existed before Europeans arrived. The Apalachee leaders and their families lived in round, palm-thatched houses bordering the central plaza where ceremonies, business dealings, and ballgames were held. The largest Apalachee building by far was the council house. In the council house, the Apalachee and their chiefs met to govern the village, consider complaints, administer justice, conduct traditional rituals, and receive visitors.

Today, the site of the San Luis’ political and religious center is a National Historic Landmark and an important archeological resource. The State of Florida bought the land in 1983 and two decades later established a historical park, where visitors can learn about the history and explore recreations of Spanish and Apalachee buildings as they looked during the 17th century.

Mission San Luis de Apalachee. The structure on the left is a reconstruction of the Council House. The one on the right is a reconstruction of the Chief’s House.

Image courtesy of Roy Winkelman and the Florida Center for Instructional Technology

Shatter Zone: Mission San Luis Abandoned

In 1702, the European War of Spanish Succession spread to Florida. The English Governor of South Carolina, James Moore, led British soldiers and Creek allies into Spanish territory to assault Florida’s missions and forts. Moore’s invasion destroyed five Apalachee missions. Thousands of Apalachee were enslaved and taken to South Carolina. Believing that a British attack on San Luis was inevitable, the remaining Spanish colonists destroyed the town before the British had a chance to sack it. The mission was burned and abandoned on July 31, 1704. After the destruction of the Spanish population moved to St. Augustine.

English slaving raids and disease continued to decimate the Indigenous population, driving the survivors into exile. Some Apalachee temporarily relocated to Timucua Province before resettling near St. Augustine. Others migrated north into Creek territory, eventually moving back to Spanish territory and settling in a refugee mission in Pensacola in 1718.

The Apalachee Diaspora

Seeking protection under the French, the Talimali Band fled to Mobile, Alabama, and settled around Mobile Bay where they assisted in the construction Fort Louis de la Louisiane, the first capital of Louisiana. A provision in the 1763 treaty that ended the French and Indian War, France ceded all the land east of the Mississippi to England. The Apalachee, unwilling to live under English rule, requested the French to allow them to move west of the Mississippi. They were granted land on the Red River in present day Central Louisiana and the remaining members relocated to their present home in Rapides Parish.

The French also gave land in Louisiana to other Indigenous exile groups including the Pascagoula, the Taensa, the Alabama, and the Coushatta.

Apalachee Descendants in Louisiana

Talimali Band Apalachee Indians of Louisiana.

Text and Image courtesy of the Talimali Band of Apalachee Indians

This a family portrait of the great, great grandchildren of John Baptiste Vallery, who is documented as an Apalachee Indian in Catholic baptismal records in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Pictured from left to right: Julian, born 1902; Herzog, born 1904; Melissa, born 1905; Virginia, born 1894; and Francis, born 1908. Francis Vallery is the grandmother of Arthur Bennett, the current chief of Talimali Band the Apalachee Indians of Louisiana.

The history of the Apalachee struggle for federal recognition mirrors that of other marginalized Indigenous peoples. For the Apalachee, this began in 1803 with the United States purchase of Louisiana from the French. Local plantation owners petitioned the federal government for their removal. When the request was denied, slaves were put against them, and they fled into the swamps of Louisiana … the story continues, and struggle is ongoing.